Most people we’ve spoken to haven’t heard of Perthes (pronounced “Pur-theeze”, and also seen as ‘Legg-Calve-Perthes’). Usually referred to as ‘Perthes disease’ but I refuse to use the word disease because clearly it’s not something contagious, and I much prefer the word ‘condition’.

Most people we’ve spoken to haven’t heard of Perthes (pronounced “Pur-theeze”, and also seen as ‘Legg-Calve-Perthes’). Usually referred to as ‘Perthes disease’ but I refuse to use the word disease because clearly it’s not something contagious, and I much prefer the word ‘condition’.

It’s a childhood disorder, which occurs when blood supply is temporarily interrupted to the ball part (femoral head) of the hip joint. Without sufficient blood flow, the bone begins to die and the hip can become intensely inflamed and irritated.

Perthes is usually seen in children between 2 and 15 years of age, with the most common age between 4 and 9. Boys are four times more likely affected than girls. Ten percent of patients will have Perthes in both hips (referred to as bilateral Perthes disease). Usually one side is affected first and then the other side will get the disease a few years later.

How is it treated? Is it something James will grow out of?

The frustrating thing is that it’s a waiting game, without knowing what the end destination will actually look like, and what it will entail on the way. No-one can tell you what will happen next and when.

We understand ‘typically’ that there are 4 stages, described below as how I understand it in my simple terms:

- Stages 1 & 2 are when the bone is dying and then starts to fragment, which is when the joint starts to crumble/soften (and the ball could be at risk of coming out of the socket). This takes place over 1-3 years (and is where James is currently at).

- Stage 3 is when the bone starts to regenerate (‘resossification’). This can take 2-3 years.

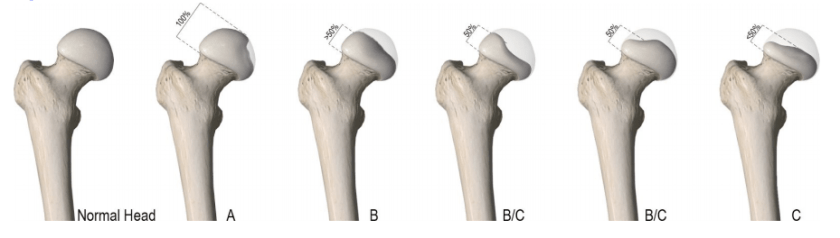

- Stage 4 is when it is ‘healed’. This means the femoral head looks similar to the normal side. However, the key thing here is ‘how’ the bone has grown back, The final shape will then give us a clue as to the long term effects of Perthes. If it grows back as a nice round ball in it’s round socket (and if James hasn’t had any operations along the way), in 5- 6 years, he might return to normal activities, and have a normal walk. If it doesn’t, he is likely to be prone to degenerative arthritis and/or need a hip replacement as a young adult. Surgical intervention could leave him with one leg shorter than the other which may leave him with a certain gait.

Why does it happen? What causes it?

Perthes is actually one of the most common hip disorders in children, however, it is still rare, with the majority of GPs only seeing one or two cases in their career. (I read somewhere that 5 in 100,000 kids get it.) GPs will generally refer straight to a Paedriatics Orthopaedic specialist to manage the condition.

It’s a strange one because it’s sometimes seemingly an invisible condition, and even in paedriatric orthopaedics, they are still trying to understand more about it. It makes it hard for people to understand it as well. They see James walking about one day, and then on crutches or in a wheelchair the next. Perthes sufferers will have good days and bad days, and usually we find with James, that he’ll be hobbling more the next day if he’s overdone it too much the day before! In order to avoid this, if we want to go somewhere that involves a lot of walking, we’ll use the wheelchair, to try and preserve James’ hip joint, damage limitation if you like, and ensure he doesn’t get pain the next day. But you can imagine the confused look on people’s faces when we get to our destination, and then James gets out and walks around as if nothing is wrong with him!

Whilst we understand what causes it (loss of blood supply), to date there still hasn’t been enough research to provide conclusive evidence as to why it happens. It does not have a strong genetic connection, with only about 5% of patients having a family member with the condition. (Although I have engaged with two sets of parents already where both their kids have it/had it!) It’s also not caused by direct hip injury. There is currently no cure for it. Like many other illnesses and conditions out there, we will now be continuously in support of all research and studies that aim to try and a) find the answers as to ‘why’ and b) be able to find a way of curing, better still, preventing it in the first place.

No parent should have to tell their little ones not to ‘run and jump’, the most natural things any child wants to do, and of course, no child, should have to have their childhood impacted by something like this. It’s felt in so many ways, small things in isolation but impactful collectively. James desperately wanted to scooter to school like the other kids, and when we finally moved house, living really close to the school, we all looked forward to that becoming a reality. Two weeks into the school term, I was back to driving him to school, and we are only a 5 minute walk away! It was also heart-breaking saying good-bye to the much loved trampoline, and I hate to think about James being the only one in his class staying behind at school when all his class mates go and have fun at Forest School.

The tail end of last year was a bumpy and emotional time, and more blog posts on that, but we started 2018 with a fresh outlook, accepting that we are a Perthes family, and now finding ways to remove those limitations, identify enablers, and simply find ways of adjusting life so we still have fun, have goals, develop new skills and create great memories.

Read the next blog to find out how 2017 ended.